Who We Are

- The Inner Temple Today

- Bench Table Orders

- Education and Qualification Rules

- Consultation Responses

- Time to Change

- We Are a Living Wage Employer

- Social Mobility Employer Index

- The Council of the Inns of Court

- Car Park Terms and Conditions

- Licensing

- Outreach Safeguarding Policy

- Applications Misconduct Policy

- 🔗 Searcys Anti-Slavery Policy

- Scholarships Feedback Policy

- Scholarships Deferrals Policy

- Modern Slavery and Human Trafficking Policy

- Environmental Policy

- Scholarships Appeals Policy

- Equality & Diversity

- Pupils Advocacy Course Appeals Policy

- PASS Travel, Accommodation and Subsistence Policy

- Anti-Bribery

- Complaints

- Privacy

- Conflicts of Interest

- Volunteer and Participant Code of Conduct

- Freedom of Information

- Admissions Database 1547-1940

- The Archives

- Bench Table Orders 1845-1945

- Calendars of Inner Temple Records 1505-1845

- The Christmas Accounts 1614-82

- The Freehold

- History of The Inner Temple Video

- In Brief

- Charles and Mary Lamb in the Inner Temple

- Grand Day

- Life in Halls: Designs of the Previous Incarnations of the Inner Temple Hall

- Gorboduc, or the Tragedy of Ferrex and Porrox

- Lord Robert Dudley, 'chief patron and defender' of the Inner Temple

- Lost in the Past : The Rediscovered Archives of Clifford's Inn

- Paintings

- Phoenix from the Ashes: The Post-War Reconstruction Of The Inner Temple

- Silver - Extract from 'A Community of Communities'

- The "Unfortunate Marriage" of Seretse Khama

- The admission of overseas students to the Inner Temple in the 19th century

- The Inns Of Court & Inns Of Chancery & their Records

- William Cowper of the Inner Temple

- William Niblett - A Life Re-Examined

- Library Manuscripts

- Paintings Collection

- Pegasus Emblem

- Silver Collection

- Our People

- Work for Us

- Notable Members

Home › Who We Are › History › Clifford’s Inn

Clifford's Inn

The Inns of Chancery were a cluster of legal institutions in the City of London which traditionally supported legal education and training of aspiring barristers, solicitors, and attorneys, as well as providing office space for clerks of the courts of chancery.

In the fifteenth century, there were ten inns in operation but by the 1900s they had all but disappeared. Clifford’s Inn, the first to emerge, and the last to be demolished, gives us a snapshot of these unique institutions, and reflects the wider history of legal education in London.

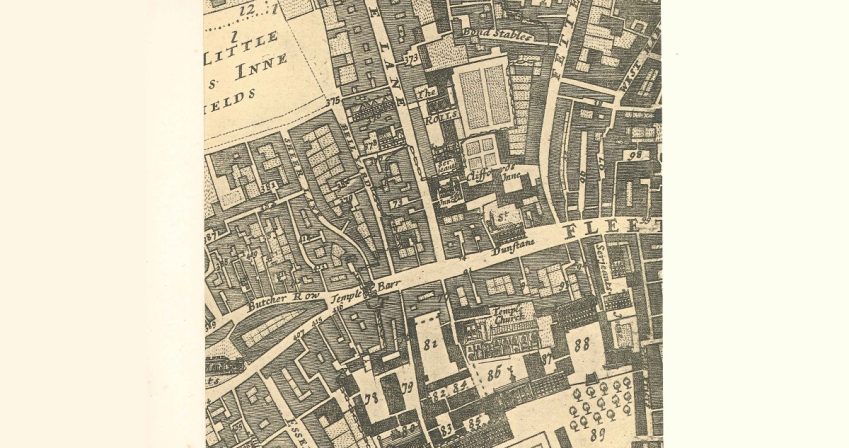

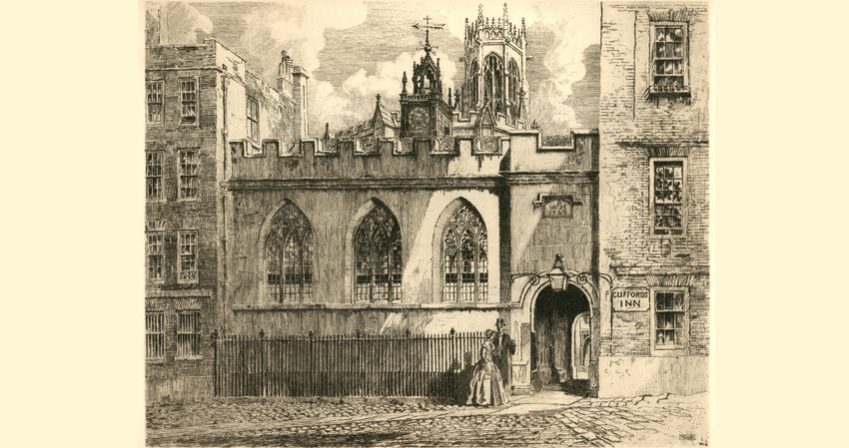

Clifford's Inn Hall, Fleet Street - Engraving

The Origins of Clifford’s Inn

The site where Clifford’s Inn once stood, is situated on Fleet Street behind the church of Saint Dunstan-in-the-West. It was granted to Robert de Clifford, third Baron Clifford, in 1310 and on his death in 1344, his widow leased the land to law students, who would have been working for and shadowing judges in the courts of chancery. At around the same time, the Inns of Court were emerging as professional bodies for barristers. The Inns of Chancery became known as the ‘lesser’ institutions over time each of them became affiliated to one of the Inns of Court. In Clifford’s case, it came to be affiliated with the Inner Temple and was effectively considered to be a satellite training centre; Inner Temple members would send readers to deliver lectures to the students on statute or common law and would adjudicate in any disciplinary matters.

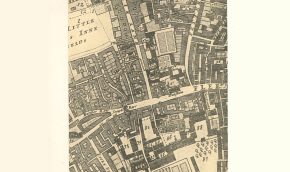

1732 - Reproduction of part of an old map by Morden & Lex showing Clifford's Inn and its surroundings. From the particulars of sale 1903

Membership and Governance

In the sixteenth century, there were around one hundred students in Clifford’s Inn. They would study for up to eighteen months, before proceeding to an Inn of Court (of their choice). Many were never actually called to the Bar and would instead become attorneys (now known as solicitors). Some of the students were sons of landowners and only required adequate knowledge of the law to help them manage their family’s estates and had never intended to become barristers.

The Inn was presided over by the Principal, elected from a body of twelve ‘Ancients’ or ‘Rules’. The rest of the membership was known as the ‘Junior’ or ‘Kentish Mess’, though the reason for that name and any connection to Kent is unknown. One of Clifford’s peculiar traditions involved four small loaves in the shape of a cross being placed in front of the Principal after dinner. The principal would throw them down three times on the table and the loaves were collected by a member at the end of the table, then taken outside the hall and given to needy recipients.

The earliest surviving statutes and ordinances of Clifford’s Inn, written in Law French, date from 1528. They were likely copied from fifteenth-century statutes and comprise forty-seven orders or regulations, ranging from the steward’s duties to bad behaviour by members, both inside and outside the Inn. A few regulations relate to the requirement to comply with the education provided in the shape of ‘learnings which belong to an inner barrister’, meaning a law student.

The Site

The site was approached from the north side of Fleet Street along a narrow alley which today is still called Clifford’s Inn Passage. On the east is the church of Saint Dunstan-in-the-West. A low crenelated archway is all that is left of the gateway to the Inn and on its walls are stone plaques commemorating eighteenth-century Principals and over the arch are the still discernible arms of the Clifford’s with their distinctive chequers. The archway led across a little courtyard called the First Court, to the hall. Accessible through the screens passage was Garden Court, described by William Maitland in 1756 as “an airy place and neatly kept, being enclosed with a palisade and adorned with rows of lime trees set around grass plats and gravel walks.” Another entrance lay on Fetter Lane east of the Church and another was on Chancery Land, beside the former Public Record Office.

To the east of the Inn’s gardens lay a four-storey range of brick-built chambers with an extension at right-angles stretching towards the Fetter Lane entrance and forming the northern side of Back Court. This L-shaped block, known as Brick or Featherstone’s Buildings, was built about 1663 and escaped damage in the Great Fire. The Principal’s chamber was at the west end of the Hall.

Clifford's Inn Hall

The Hall was re-built in 1767. Three early English gothic stained-glass windows displayed the distinctive chequers of the Clifford’s on the north and south sides. On the roof sat a little square tower with large clock-faces, and a smaller domed cupola with a weathervane.

On 29 March 1618, the members of the Inn were granted the freehold, conditional on a rent-charge of four pounds a year and certain rights of residence in favour of the Clifford family. These rights were not extinguished until 1879, when the Duke of Devonshire, as heir to the Cliffords (estate?), surrendered the rent-charge and a set of chambers at No. 10 Clifford’s Inn to the Principal and members for £850.

In addition to members, users of the site included the offices of the Marshalsea Court (abolished in 1849) which were at at No. 14 Clifford’s Inn. The Inn’s hall also hosted the Fire Commissioners in 1666, which was appointed to hear and determine disputes relating to property boundaries and other matters caused by the rebuilding of the City after the Great Fire. Four of the judges’ portraits now hang in the Hall of The Inner Temple. The Hall was also used by the Society of Gentlemen Practisers in the Courts of Law and Equity, founded in 1739 to represent attorneys, and precursor to the Law Society, the professional body of solicitors established in 1825.

Decline

There were a few factors which led to the slow decline of the Inns of Chancery, and therefore Clifford’s Inn. The first sign was in 1547, the Duke of Somerset and uncle of King Edward VI, demolished one of the Inns (Strand Inn) to make room for a ‘residence suitable to his high rank’ that is a grand home for himself which would welcome notable individuals. The building became known as Somerset House.

The English Civil War also contributed to the slow decline of the Inns of Chancery as educational institutions and hastened the growing membership of the Inn by attorneys, as opposed to students. At Clifford’s Inn, readings delivered by members of the Inner Temple still took place, but these were increasingly seen as a formality, and by the nineteenth century the readers’ appointments were ignored by the Inn. By this time there were few, if any, law students and the Inns of Chancery had devolved into glorified dining societies. Unlike the Inns of Court, the Inns of chancery didn’t hold a monopoly on legal education, and other professional bodies, such as the Law Society became more relevant attracting higher number of students.

Nonetheless, the Inner Temple attempted to assert control over Clifford’s and the matter came to a head in the case of R. v. Allen in 1834. John Sympson Jessop, a barrister of the Inner Temple and a Rule (governor) of Clifford’s Inn, brought an action for mandamus against the Principal of Clifford’s Inn, William Henry Allen. It required Allen’s attendance at a meeting of the Inner Temple Benchers to decide the validity of his election as Principal. Allen refused to attend. The court found that Clifford’s Inn was older than the Inner Temple and had never been subservient to it and furthermore that the Inner Temple had never claimed or exercised such jurisdiction. By then, the inn was almost exclusively the domain of attorneys and solicitors rather than students wishing to progress to the Bar.

A loss in relevance and purpose was made worse by a synchronous decline in membership. Two registers of attendance at dinner in hall, dating from 1873 to 1891 show the same names repeated frequently but irregularly in falling numbers until they expire on 6 February 1891. In 1885, an attempt was made to establish a written constitution and merge the Rules and the Kentish Mess, but this could only come into effect when executed by six-sevenths of the membership and that majority was never reached. Eight signatures are recorded and nine are missing. A noticeable absentee was George Booth, a solicitor admitted in 1849, who, in one of his final professional acts, would carry out the winding up and sale of Clifford’s Inn.

By 1899, with only sixteen members left, some had decided to sell the Inn and divide the proceeds amongst themselves. Other members disputed the legality of this and successfully proved in court that the Inn was a charity. The Inn was, however, sold in 1903 to William Willetts for £100,000. Some £70,000 were allocated to legal education and to this day the Law Society provides a prize known as the Clifford’s Inn Prize to suitable candidates in the solicitors’ examinations.

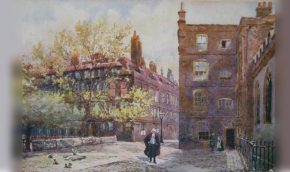

From the particulars of sale 1903. Shows the north side of Clifford's Inn, the solicitors and the auctioneers

The Society of Knights Bachelor bought the Hall and some adjoining buildings in 1911. During the First World War, the premises were used by the Army as offices for the Army Spectacle Depot. In 1921 the Society moved to Lincoln’s Inn and put Clifford’s up for auction, but the Inn failed to reach the reserve price and the buildings were demolished in 1934 to make way for a block of flats.

Legacy

Over the years the Inn was home to numerous celebrated members. They range from Edmund Paston of the Paston Letters in the fifteenth century, to Sir Edward Coke (1552–1634), who was admitted in 1571 and went on to become Lord Chief Justice. John Selden (1584–1654), admitted in 1602, was a great scholar and jurist. A more infamous member was George Jeffreys, (1644–89), the Lord Chief Justice who presided over the Bloody Assizes, a series of trials which came after Monmouth’s uprising in 1685. George Edwards (1694–1773), known as the father of British ornithology, lived in the Inn in the late eighteenth century. George Dyer (1755–1841), poet and friend of Charles Lamb, lived in the Inn for many years. The novelist Samuel Butler (1835–1902) wrote The Way of all Flesh during his tenancy of No. 15 Clifford’s Inn from 1864 to 1902. Literary couple, Virginia and Leonard Woolf, were tenants in 1913 and found their chambers to be “incredibly draughty and dirty and a gentle rain of smuts fell”, so that “a thin veil of smuts covered the paper before you had finished a page”. When the last members of Clifford’s Inn sold the building in 1903, it was acquired by developer William Willet, the father of daylight-saving time.

In literature, Charles Dickens referred to the Inns of Chancery several times in his works. In The Pickwick Papers, the Inns are described as “singular old places” and the skeleton of a deceased resident, who nobody seemed to have missed, was found in a cupboard clasping a bottle of arsenic. In Our Mutual Friend, Clifford’s Inn is described as

the mouldy little plantation, or cat preserve … Sparrows were there, cats were there, dry rot and wet rot, but it was not otherwise a suggestive spot.

Our Mutual FriendUntil 1998, the only documents thought to survive from Clifford’s Inn were an account book of 1738–49, extracts from the Minute Books of 1609–1740, two dinner registers and the fifteenth-century Statutes and Ordinances. Interest in Clifford’s Inn was revived in 1998, when a large collection of documents was discovered in the basement of No. 4 Brick Court, Middle Temple, then the offices of a firm of solicitors, George Thatcher & Sons. It is presumed that the documents were entrusted to George Thatcher by his partner, the aforementioned George Booth, one of the last Clifford’s Inn members and the solicitor who carried out the sale of the building.

The collection is now supplemented by varied administrative documents, including title deeds from 1618, plans for rebuilding and particulars of the auction. The real value of the collection, however, lies in the names of the members of the Inn from 1572 to the late nineteenth century. With this information it has been possible to compile a list (though probably incomplete) of the Inn’s Principals, from Nicholas Sulyard, the earliest recorded Principal in 1618, to the last, David Henry Stone, a solicitor turned London Lord Mayor in 1874.

One surviving vestige is a length of oak panelling with rich ornamentation over the door-cases installed in 1688 by John Penhallow, who was admitted to the Inn in 1674 and whose coat-of-arms appears on the chimney-piece was once part of chambers at No. 3. It is now on display at the Victoria and Albert Museum.