Extract from

The Inner Temple: A Community of Communities

by John Deby QC, Master of the Silver 1991 - 2012

Most people would expect the Inns of Court, like the City Livery Companies and Oxford and Cambridge Colleges, to have gathered together a large collection of silver over the centuries. There have, however, been both additions and disposals. Additions have come mainly from gifts by Treasurers and other Benchers, with pride of place going to Master Schiller who was Treasurer in 1942 and bequeathed to the Inn in 1947 a very high proportion of the present collection.

The Inn itself must have purchased items of silver from time to time but the Inner Temple records make little reference to silver. There is, however, an entry in the contemporary account book recording the joint purchase with Middle Temple of what must have been a very splendid cup to give to James I in 1608 as a “thank you” for the Royal Charter. Alas, the cup was pawned in Holland by Charles I and never redeemed, and has not since been traced.

On the debit side, silver is sometimes sold or melted down. All the silver (except Church Plate) was melted down in the Civil War; changes of fashion doubtless led to pieces being melted down and remodelled; items were sold when money was needed, in particular in the last century to fund student scholarships.

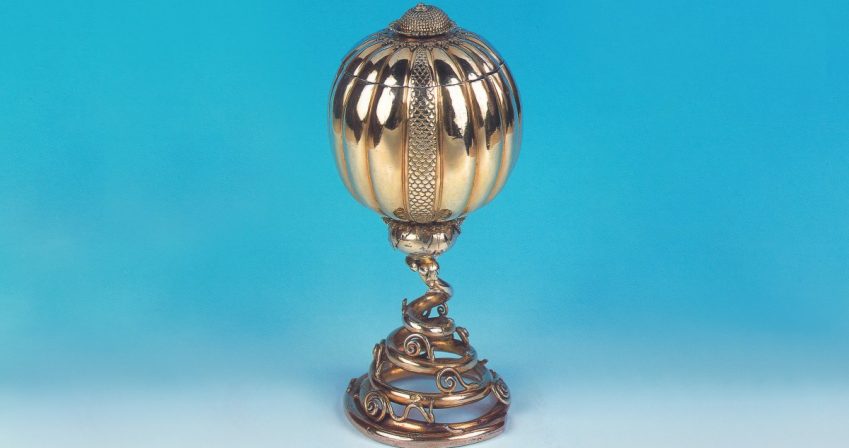

In this article I can only refer to some of the more interesting items in the collection. The piece we have had for the longest time is a silver-gilt chalice, which is one of a pair. They were supplied by Terry in 1609, the year after the Royal Charter, and the account book reads: “To Terry, a goldsmith, for two new communion cups for the Temple Church, abating of the exchange of one old one, 13li 12s 2d; the Middle Temple paid the one half, 6li 16s 1d.”