First woman to be called to the Bar of England and Wales

Women in Law

- Introduction

- Timeline

- Joyce Bamford-Addo

- Marion Billson

- Jill Black

- Elizabeth Butler-Sloss

- Sue Carr

- Eugenia Charles

- Lynda Clark

- Freda Corbet

- Coomee Rustom Dantra

- Leeona Dorrian

- Heather Hallett

- Frene Ginwala

- Rosalyn Higgins

- Daw Phar Hmee

- Lim Beng Hong

- Dorothy Knight Dix

- Sara Lawson

- Elizabeth Lane

- Theodora Llewelyn Davies

- Gladys Ramsarran

- Lucy See

- Evelyn Sharp

- Victoria Sharp

- Ingrid Simler

- Teo Soon Kim

- Ivy Williams

- The Significance of the Sex Disqualification (Removal) Act 1919

- Podcasts

Home › Women in Law › Our Women › Ivy Williams

Dr Ivy Williams

Admitted 1920, Called 1922

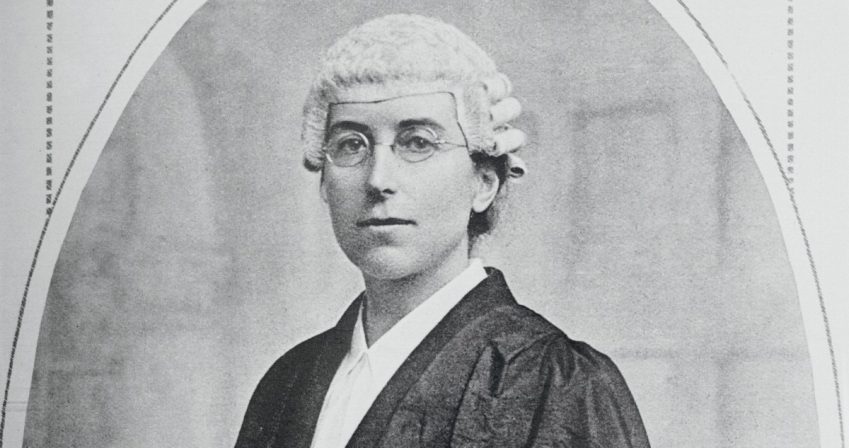

Dr Ivy Williams occupies a special place in the world of women, firsts, and law. On 10 May 1922 she became the first woman to be called to the Bar of England and Wales. Her Call night at Inner Temple was reported in newspapers all over the world, varying in their focus on her appearance and dress: clothed in black dress under her barrister’s gown, she was said to be ‘not a giddy young thing’; her brilliance: she held the position of Senior Student and made the address in reply to the Common Serjeant; and her cool and collected demeanour.[1]

Henry Dickens, the Common Serjeant, referred to her as an ‘apparition’[2] in his address to the newly-called barristers. This was an apt description of her life at the Bar, which ended as soon as it began. Dr Williams soon faded from view, while the rest of her cohort, including Helena Normanton QC and Sybil Campbell, the first woman full-time judge, were called in November 1922. While they began the struggle to be accepted and survive as barristers, Dr Williams returned to her position as Tutor in Jurisprudence for the Oxford Society of Home-Students, a position she held from 1920 till her retirement in 1945.

Ivy Williams was born in 1877 in the small town of Newton Abbott in Devon. Her parents, George St Swithin Williams and Emma Ewers, both originally from Oxford, were living there after moving from the Isle of Wight where their first child Winter was born in 1875. This was possibly to escape familial disapproval of their unusual romance. George was 21 years older than Emma; they met when she was working for his family as their maid. No records can be found determining whether George and Emma ever married. The little family returned to Oxford in 1880 following the death of George’s father Adin Williams in 1876.

Oxford degrees for women. Miss Ivy Williams the first woman graduate to receive Oxford Degrees. She is a B.A., N.A., B.C.L. Dr Ivy Williams was the first woman to be called to the English Bar on the 10 May 1922, although she never practised as a barrister. 14 October 1920

Ivy Williams’ Call to the Bar had been the fulfilment of a childhood dream: both her father and her brother were lawyers; her father a solicitor and her brother a barrister, also of Inner Temple. She entered Oxford to study Jurisprudence in 1896, completing her exams for the BA in Jurisprudence in 1900 with a second class pass and the BCL in 1902. She also obtained an LLB in 1901 and an LLD in 1903 from the University of London, which unlike Oxford, awarded degrees to women. Although well qualified in law, she could not practise. Entry to both branches of the legal profession was closed to women until the passage of the Sex Discrimination (Removal) Act 1919.

Ivy Williams was admitted to the Inner Temple in January 1920. She took her first Bar exams in the Trinity term of 1920. Her final score for her Bar exams was 475. This was a first class pass, which placed her second of 123 candidates. The Inns of Court regulations rewarded her with a Certificate of Honour, 105 guineas, and an exemption from two terms’ of dinners. In this way, she was able to accelerate her Call to the Bar and become the first woman to be called to the Bar of England and Wales. But she had already decided not to forge a career at the Bar, citing her age as the reason why.[3] She took the opportunity of this private but very publicised moment of her Call to speak ‘of the women who would follow and practise at the Bar, and she asked that every help and encouragement should be given to them in the difficulties they would face.’[4]

Returning to Oxford, where she had been the first woman to be appointed to teach law in the UK, Dr Williams’ academic work focussed on Swiss private law. Fluent in several languages, she authored two books in quick succession: The Sources of Law in the Swiss Civil Code (1923) and The Swiss Civil Code (1925). For the former, she was awarded the Oxford DCL, the first woman to have been honoured with this degree. These works are still referred to in academic writings today, a testament to their usefulness and quality. Her scholarly career was cut short by a skiing accident that left her ‘laid up for some years’[5] as she wrote to Sybil Campbell in 1929. Dr Ivy Williams was remembered by her students as someone who

let us go our own ways with splendid objectivity… beneath a shy and remote exterior she concealed a personality that was both kind and courageous…. It was not until many years later that those who had kept in touch with her learnt to delight freely in the range of her keen intelligence…[6]

She also gave of her time and legal knowledge in the service of the public. In 1930, through her work with the British Federation of University Women, she was appointed as a technical delegate to the Conference on the Codification of International Law. Her work there on the question of married women’s nationality law was favourably received, government officials describing her as ‘posess[ing] a very sound and balanced judgement’.[7] As a result, Dr Williams was appointed to the Aliens Deportation Advisory Committee in 1932. The Committee became a thorn in the side of the government, advising against deportation in almost half of all cases that came before it; its activities were effectively curtailed in 1936, and it was formally disestablished in 1939.[8]

Ivy Williams, via Getty Images

Little is known of Dr Williams’ private life. We do know that she came from a strongly religious background. Her family were Congregationalists and many served as missionaries in Africa and the Pacific. She was a generous supporter of Oxford University, providing money for two scholarships in her brother’s name as well as for lodgings for women students. She also gave land to the Radcliffe Hospital and the local Congregationalist church in Cowley. She never married or had children. She lived for many years with Nora MacMunn, a lecturer in Geography for the Society of Home-Students, but the nature of their relationship is unknown.

Dr Ivy Williams died at the age of 88 at her home in Oxford. In the later years of her life she had become frail and had lost her sight. In retirement, she remained active in the service of others, teaching herself Braille, writing a Braille primer and creating a Braille reading course for the Royal National Institute for the Blind.

Dr Ivy Williams’ death was not marked by the fanfare of publicity that accompanied her Call. Apart from a short obituary in The Times, her death passed largely unmarked in the press. In commemorating Dr Ivy Williams in this exhibition, it is hoped that this short remembrance will remind us of and re-establish to her rightful place a woman who was, by her achievements in law and her work in legal education and public service, played more than her part ‘in the slow and difficult advance of women to their present position in the legal profession and in the universities.’[9]

Dr Caroline Morris

Department of Law, Queen Mary University of London.

[1] Evan Griffiths ‘The British Novelty’ Pittsburgh Post-Gazette (24 July 1922) p6.

[2] ‘First Woman to be Called to the Bar’, undated, Newspaper Clippings, St Anne’s College Archives.

[3] ‘First Englishwoman Barrister’ The Guardian (11 May 1922) p6.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Letter, Ivy Williams to Sybil Campbell, 6 December 1929, LSE Women’s Library Collection 5BFW/03/08.

[6] S Penley and EO Dodgson, ‘Dr Ivy Williams: An Appreciation’ (1966) The Ship 37, 38.

[7] National Archives File HO 45/14909: Aliens Deportation Advisory Committee: appointment of members, rules and minutes of proceedings.

[8] David Bonner, Executive Measures: Terrorism and National Security (Ashgate, Aldershot, 2007) 119.

[9] S Penley and EO Dodgson, ‘Dr Ivy Williams: An Appreciation’ (1966) The Ship 37-38.