In this list of pioneers, Lim Beng Hong stands out for the number of gender barriers she broke.

Women in Law

- Introduction

- Timeline

- Joyce Bamford-Addo

- Marion Billson

- Jill Black

- Elizabeth Butler-Sloss

- Sue Carr

- Eugenia Charles

- Lynda Clark

- Freda Corbet

- Coomee Rustom Dantra

- Leeona Dorrian

- Heather Hallett

- Frene Ginwala

- Rosalyn Higgins

- Daw Phar Hmee

- Lim Beng Hong

- Dorothy Knight Dix

- Sara Lawson

- Elizabeth Lane

- Theodora Llewelyn Davies

- Gladys Ramsarran

- Lucy See

- Evelyn Sharp

- Victoria Sharp

- Ingrid Simler

- Teo Soon Kim

- Ivy Williams

- The Significance of the Sex Disqualification (Removal) Act 1919

- Podcasts

Home › Women in Law › Our Women › Lim Beng Hong

Lim Beng Hong

(later Oon Beng Hong OBE, known as Mrs B H Oon, 1903-1979)

Admitted 1923, Called 1926

Born in Penang, British Malaya, she was the first ethnically Chinese woman to hold a degree from University College, London; the first to be called to the English Bar; the first to be called to the Straits Settlements Bar; and the first female member of the Federal Legislative Council, the forerunner of the Malaysian Parliament.

Lim’s father was a merchant, and the family was wealthy. She was educated at the Government Girls’ School in Penang; after finishing, she returned there to teach for a few years before leaving to study law in England along with her brother, Lim Beng Tek. She may have been inspired in her decision by her brother-in-law, Goh Guan Ho, who had studied law at the University of London and had been called to the Bar from Lincoln’s Inn in 1916.

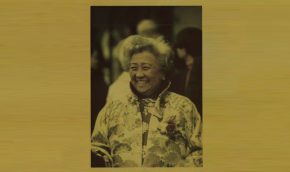

Mrs BH Oon. Image source: 'Historical personalities of Penang' by Historical Personalities of Penang Committee.

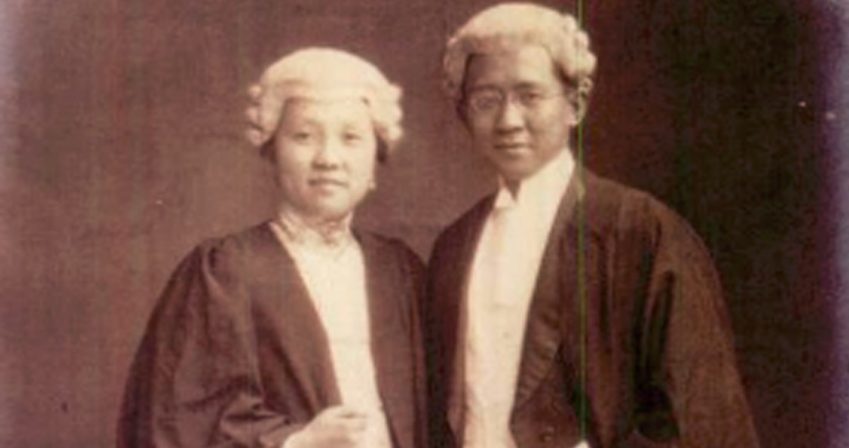

Lim Beng Hong and Lim Khye Seng in gowns and wigs crop

Most probably thanks to their family’s wealth and social status, the Lims were able to obtain references from pillars of the local colonial establishment. One was written by Major General Sir Neill Malcolm, commander of British forces in Malaya, and the other was from P J Sproule, a puisne judge at the Supreme Court of the Straits Settlements. Maj Gen Malcolm stated in his letter that he had only known Lim Beng Hong for a year, but he clearly knew the family well enough to stand in for her father by giving her away at her wedding in 1927. Malcolm also wrote in support of Teo Soon Kim, another young Chinese woman from the Straits Settlements who was admitted to and called to The Inner Temple close on the heels of her compatriot.

Sproule’s letter indicated that the Lims planned to enter Middle Temple, of which Sproule himself was a member. However, for reasons which are not clear, the pair changed their plans and were admitted instead to Inner Temple. In fact, Lim’s brother was admitted to Inner Temple a few months after her, but the two were called to the English Bar on the very same night in June 1926. The same thing happened the next year when they were simultaneously called to the Straits Settlements Bar in Penang. Their younger sister Beng Tek Lim followed them to The Inner Temple in 1930, and was called four years later.

Lim returned to Penang a year after her Call to be married to Oon Guan Yong. Thereafter she preferred to be known as Mrs B H Oon. Perhaps unusually for the time and place, she continued to lead an active public life after her marriage. She joined the firm of Lim and Lim, Advocates and Solicitors, and applied to join the Bar of the Straits Settlements and the Federated Malay States. The law in British Malaya still forbade the admission of women: this was amended in 1927 and Mrs Oon was the first Asian woman to be admitted. However, the legality of the amendment remained in dispute until 1935, when it was finally approved by the chief justice of the Kuala Lumpur Supreme Court.

At the outbreak of the Second World War, Mrs Oon left her home in Butterworth, Penang and sought refuge in the British fortress of Singapore. By February 1942, evacuated from Singapore to Java just before the fall. Allied forces on Java surrendered in March 1942, and all Europeans on the island were interned by the Japanese occupiers. The Asian population remained at liberty, though subject to the constraints of the occupying military government. Mrs Oon used her freedom to smuggle letters from captive Europeans on Java to POWs held in Changi Prison on Singapore.

After the war, Mrs Oon was appointed as one of only two female members of the Federal Legislative Council, an embryonic parliament which gave the citizens of all ethnicities a voice. The FLC was one of the key prerequisites for Malaysia’s eventual independence from British colonial rule. She served on the Council from 1948 to 1955. Afterwards, she became active in local politics, serving as a local Labour Party councillor in her hometown of Butterworth, Penang. She also created the Women’s Charter which was included in the electoral manifesto of the Pan-Malayan Labour Party. In 1953, her contribution to Malayan national life was recognised by her appointment to the Order of the British Empire. In 1971 she was elected as the first Malaysian President of the International Federation of Women Lawyers.